Making Linux C++ Crashes Less Chaotic

Fear the dreaded “Segmentation fault (core dumped)”? Here’s how I stopped worrying and learned to love the crash.

This is a write up of some of what I found in adding crash handling in a complex mutli-threaded C++ application for my day job. A lot of this was learned through trial and error, and should not be taken as gospel. I also imagine that some of these details are specific to environment I was working in (CPU, OS, kernel, compiler, etc.).

For reference this was tested on Ubuntu 2022 with GCC 11.2 on x86-64 and ARM64 devices.

Also see the follow up articles on:

What is Crash Handling?

For the purposes of this discussion, a crash is when the process tries to execute an invalid operation (write a null pointer, read an invalid address, etc.), or when an abort is triggered (from an assert, exception, etc.). There’s a ton of other errors that would require diagnostics and handling, but this discussion is meant to handle fatal errors that indicate the application is in an invalid state.

This sort of handling should be an approach of last resort. Ideally, these sorts of crashes should never happen. Either you’re using a memory safe language that doesn’t (normally) generate these crashes, or your code is hardened to the point where they should be vanishingly rare. In the case they do happen, the default core dump with a mechanism for the user to report the error should be sufficient.

However, the use case I was building for was for an extremely complicated C++ application in an IoT device. While it was possible to sometimes upload the full core dump, we wanted to always be able to grab a stack trace and the last logging output to get some information about the cause of the crash. The handling described here is mostly intended to be exercised integration and beta testing setups used to evaluate builds during development.

The basic goal how this crash handling recover as much diagnostic information as possible. This can be done with the following actions in order of priority:

- Exit without a large delay with a meaningful exit code.

- Generate a core dump.

- Record the backtrace of the source of the crash.

- Give the application a chance to shut down gracefully, but to avoid deadlocking if the crash prevented graceful shutdown (an mutex is locked).

Note on Generating Backtrace

As I go into more detail on in Using Backtraces, generating a backtrace during a has a non-zero possibility of deadlocking. While I haven’t seen it in practice with the methods I’m using, it is likely that goal 3. above conflicts with goal 1. above.

Linux Crash Signals

I’ve generally never had to think too deeply about Linux signals. I’ve pretty much only ever considered them if an application needed to catch ctrl+c (SIGINT) to exit gracefully.

When a process “crashes” typically one of the steps in the OS handling the error is to raise a signal. The Linux signals list indicates that certain signals result in a “Core” action. By default these “terminate the process and dump core”.

The following signals default to the core action:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

SIGABRT P1990 Core Abort signal from abort(3)

SIGBUS P2001 Core Bus error (bad memory access)

SIGFPE P1990 Core Floating-point exception

SIGILL P1990 Core Illegal Instruction

SIGIOT - Core IOT trap. A synonym for SIGABRT

SIGQUIT P1990 Core Quit from keyboard

SIGSEGV P1990 Core Invalid memory reference

SIGSYS P2001 Core Bad system call (SVr4);

see also seccomp(2)

SIGTRAP P2001 Core Trace/breakpoint trap

SIGUNUSED - Core Synonymous with SIGSYS

SIGXCPU P2001 Core CPU time limit exceeded (4.2BSD);

see setrlimit(2)

SIGXFSZ P2001 Core File size limit exceeded (4.2BSD);

see setrlimit(2)

Common example of this would be:

1

2

3

4

char* BAD_PTR = reinterpret_cast<char*>(0);

*BAD_PTR = 10; // Triggers segmentation fault (SIGSEGV)

assert(0); // Triggers abort (SIGABRT)

Will discuss signal handling in more detail later, but for now we can think of these signals as interrupts the process to generate the core dump and exit.

What “Normally” Happens

Let’s use a slightly more complicated example application:

https://github.com/axlan/crash_tutorial/blob/master/src/example1/uncaught_exception.cpp

Here we’re generating an unhandled exception.

Exceptions actually have an extra layer of failure handling. Instead of directly calling abort(), they call a terminate function that can be set to a custom handler.

Running the example results in the following output:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

> build/example1

Hello World.

Terminated due to exception: Something went wrong

thread...

thread...

thread...

thread...

[1] 70681 IOT instruction (core dumped) build/example1

“IOT instruction” is just an alias for abort.

The other thing to note, is that terminate doesn’t affect other threads. We could signal the other thread to clean up, then exit with whatever error code we want. This would avoid generating an abort and a core dump.

I’ll link to a more in depth discussion of this later, but for now let’s look at the backtrace from debugging the core dump:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

#0 __pthread_kill_implementation (no_tid=0, signo=6, threadid=134684544119744) at ./nptl/pthread_kill.c:44

#1 __pthread_kill_internal (signo=6, threadid=134684544119744) at ./nptl/pthread_kill.c:78

#2 __GI___pthread_kill (threadid=134684544119744, signo=signo@entry=6) at ./nptl/pthread_kill.c:89

#3 0x00007a7eb0042476 in __GI_raise (sig=sig@entry=6) at ../sysdeps/posix/raise.c:26

#4 0x00007a7eb00287f3 in __GI_abort () at ./stdlib/abort.c:79

#5 0x00007a7eb04a2753 in ?? () from /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libstdc++.so.6

#6 0x00007a7eb04ae277 in std::terminate() () from /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libstdc++.so.6

#7 0x00007a7eb04ae4d8 in __cxa_throw () from /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libstdc++.so.6

#8 0x00000000004027d5 in main () at /src/crash_tutorial/src/example1/uncaught_exception.cpp:33

The relevant portion is that our exception, triggered std::terminate(). It called our custom function which printed the exception. Since the custom function didn’t exit the process, std::terminate() finished with it’s default action of calling abort().

Analyzing Core Dumps

In my opinion core dumps are the single most useful tool in analyzing a crash. I’ve split out this section into its own page:

Overriding the Default Signal Handlers

Let’s say we want to log a backtrace of the crash source before the program exits even in the case of a segfault. The following code provides an example of this:

https://github.com/axlan/crash_tutorial/blob/master/src/example2/handle_signal.cpp

Handling Signals in Multi-Threaded C++ Applications

The following section talks about overriding the signal handler. This is really only “safe” if this is just used to to some very limited action before terminating. For a much better approach to multi-threaded signal handling, see https://thomastrapp.com/posts/signal-handlers-for-multithreaded-c++/ . This article gives multiple strategies to detect signals and handle them from a thread when it’s in a well defined state to avoid the synchronization issues mentioned below. This is great for better handling of SIGINT or SIGTERM sent to the process. However, we’ll take the simple approach for this basic example.

We can register a function to be called when the process receives or triggers a signal. This gets pretty complicated when it comes to multi-threading. For now we’ll focus on the simplest example where we just set a global signal handler. This is an area I’m particularly unclear on. From stackoverflow:

Do the other threads continue executing when a signal arrives?

On Linux they do because a signal is only ever delivered to one thread. Unless the signal is SIGSTOP, which stops all threads of a process. See man signal(7) and man pthreads(7) for more details (ignore LinuxThreads info related to old threads implementation).

Although POSIX does not require that, so these details are OS specific.

From my experience when a crash is triggered, it will just interrupt the thread that performed the invalid operation. Since signal handling can interrupt the threads of execution during critical sections where locks or global variables are in intermediate states. For instance a call to malloc might be holding its lock causing any memory allocations in the thread handler to deadlock.

Only an extremely small set of functions are considered safe within a signal handler: https://www.man7.org/linux/man-pages/man7/signal-safety.7.html

The main issue for using functions that aren’t in that list, is that:

- Some functions (like spawning a new thread) will just not work at all.

- Any functions that have global state (which includes any dynamic memory allocations) might be in an unexpected state if the signal interrupted the thread while it was manipulating that state.

Returning from the signal handler will repeat the same instruction and just retrigger the signal. In this case there is no safe way to perform arbitrary cleanup operations since there’s no way to cleanup the locks/resources that were being used by the failed thread.

Running the example results in the following output:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

> build/example2

Hello World.

*** FatalSignalHandler stack trace: ***

build/example2(_Z18FatalSignalHandleri+0x58)[0x402544]

/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6(+0x42520)[0x7aef88842520]

build/example2(main+0xb3)[0x402697]

/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6(+0x29d90)[0x7aef88829d90]

/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6(__libc_start_main+0x80)[0x7aef88829e40]

build/example2(_start+0x25)[0x402355]

thread...

thread...

thread...

thread...

thread...

thread...

thread...

thread...

thread...

[1] 147406 segmentation fault (core dumped) build/example2

From the print outs, we see once again that the other thread kept running while we were handling the signal. We also see the stack trace printed, but it probably doesn’t look too useful.

The lines that start with build/example2 correspond to code in the binary we compiled. Of those build/example2(main+0xb3)[0x402697] is 0xb3 bytes from the start of our main() function. I’ll cover this in a bit more detail later, but we can use the tool addr2line to get the line number:

1

2

3

> addr2line -f -C -i -e build/example2 0x402697

main

/src/crash_tutorial/src/example2/handle_signal.cpp:61

Which matches the line that wrote to a NULL pointer.

Looking at the backtrace in the core dump gives a matching result:

1

2

#0 main () at /src/crash_tutorial/src/example2/handle_signal.cpp:61

61 *BAD_PTR = 10;

Backtraces From C++ Applications

Every time I need to set up getting a backtrace from a C++ application I’m amazed at how difficult it is. Generally, I’d advise against trying to do this unless you really can’t use a debugger or a core dump. I’ve split out this section into its own page:

Handling Cleanup After a Crash

Now let’s look at adding a mechanism for attempting graceful cleanup:

https://github.com/axlan/crash_tutorial/blob/master/src/example3/try_cleanup.cpp

While this example doesn’t really do anything in its cleanup process, you could imagine dumping a circular buffer of data, flushing logs, or cleanly disconnecting from external resources.

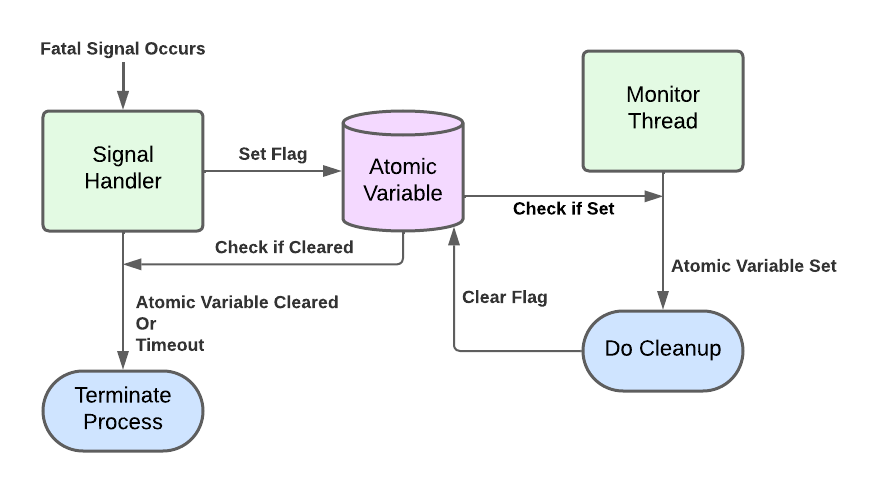

After a fatal signal is triggered, the process is going to be in an invalid state. Memory allocations might deadlock, and almost nothing is guaranteed to work correctly. While the signal handler and the thread that triggered it are almost certainly in a unrecoverable state, other threads have a reasonable chance of being in a workable state. There’s a balancing act of trying to gather additional diagnostic information, while still making sure that the process exits correctly.

My approach is the following:

Since the signal handler doesn’t need to do any “unsafe” operations, and will terminate the process on a timeout, we don’t need to worry about the cleanup thread locking up. However, if the cleanup process also crashes, we may need to handle that crash as well. In this simple example, that case ends up working out. The original crash will timeout before the second one. Also, since the second crash locks out the monitor thread, we don’t get additional cleanup attempts.

Output from running the example with a successful cleanup:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

> build/example3

thread...

Hello World.

*** FatalSignalHandler stack trace: ***

build/example3(_Z18FatalSignalHandleri+0x52)[0x4027f7]

/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6(+0x42520)[0x70b133e42520]

build/example3(main+0x1ee)[0x402b81]

/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6(+0x29d90)[0x70b133e29d90]

/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6(__libc_start_main+0x80)[0x70b133e29e40]

build/example3(_start+0x25)[0x4024b5]

Fault detected, shutting down.

Dummy exiting.

Shutdown complete.

[1] 147106 segmentation fault (core dumped) build/example3

Output from running the example with a cleanup that locks up:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

> build/example3 a

thread...

Hello World.

*** FatalSignalHandler stack trace: ***

build/example3(_Z18FatalSignalHandleri+0x52)[0x4027f7]

/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6(+0x42520)[0x71c79aa42520]

build/example3(main+0x1ee)[0x402b81]

/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6(+0x29d90)[0x71c79aa29d90]

/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6(__libc_start_main+0x80)[0x71c79aa29e40]

build/example3(_start+0x25)[0x4024b5]

Fault detected, shutting down.

Cleanup blocked.

[1] 147150 segmentation fault (core dumped) build/example3 a

Output from running the example with a cleanup that crashes:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

> build/example3 a a

thread...

Hello World.

*** FatalSignalHandler stack trace: ***

build/example3(_Z18FatalSignalHandleri+0x52)[0x4027f7]

/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6(+0x42520)[0x7bb93fa42520]

build/example3(main+0x1ee)[0x402b81]

/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6(+0x29d90)[0x7bb93fa29d90]

/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6(__libc_start_main+0x80)[0x7bb93fa29e40]

build/example3(_start+0x25)[0x4024b5]

Fault detected, shutting down.

example3: /src/crash_tutorial/src/example3/try_cleanup.cpp:92: main(int, char**)::<lambda()>: Assertion `cleanup_action != CleanupType::CRASH' failed.

*** FatalSignalHandler stack trace: ***

build/example3(_Z18FatalSignalHandleri+0x52)[0x4027f7]

/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6(+0x42520)[0x7bb93fa42520]

/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6(pthread_kill+0x12c)[0x7bb93fa969fc]

/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6(raise+0x16)[0x7bb93fa42476]

/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6(abort+0xd3)[0x7bb93fa287f3]

/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6(+0x2871b)[0x7bb93fa2871b]

/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6(+0x39e96)[0x7bb93fa39e96]

build/example3[0x402d87]

build/example3[0x402efd]

/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libstdc++.so.6(+0xdc253)[0x7bb93fedc253]

/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6(+0x94ac3)[0x7bb93fa94ac3]

/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6(+0x126850)[0x7bb93fb26850]

[1] 148602 segmentation fault (core dumped) build/example3 a a

We can see in all these cases, the first stack trace is the same. This matches the stack trace from the core dump in all 3 cases as well:

1

2

3

> addr2line -f -C -i -e build/example3 0x402b81

main

/src/crash_tutorial/src/example3/try_cleanup.cpp:121

1

2

3

#0 main (argc=<optimized out>, argv=<optimized out>)

at /src/crash_tutorial/src/example3/try_cleanup.cpp:121

121 *BAD_PTR = 10;

The stack trace from the assert is a bit more complicated since it was from an inline lambda function:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

> addr2line -f -C -i -e build/example3 0x402d87

std::basic_ostream<char, std::char_traits<char> >& std::operator<< <std::char_traits<char> >(std::basic_ostream<char, std::char_traits<char> >&, char const*)

/usr/include/c++/11/ostream:616

operator()

/src/crash_tutorial/src/example3/try_cleanup.cpp:94

> addr2line -f -C -i -e build/example3 0x402efd

std::thread::_State_impl<std::thread::_Invoker<std::tuple<main::{lambda()#1}> > >::_M_run()

/usr/include/c++/11/bits/std_thread.h:211

It sort of makes sense, we can see it’s triggered from a thread invoked from a lambda, but the final instruction is slightly off. This happens even when I turn off optimizations completely, and even if it’s the first crash to trigger. My best guess is this is a complication from the inlined lambda code, and shows that even with the stuff “figured out” there can still be complications.

Making an Abomination

So with all this in mind I made a awful example that shows how you could make a unit testing framework that can handle fatal errors without exiting, and even check to make sure they occur:

https://github.com/axlan/crash_tutorial/blob/master/src/example4/abomination.cpp

The tests are:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

std::cout << "Test 1: "

<< TestResultToString(CheckIfAborts([]() { abort(); }))

<< std::endl;

std::cout << "Test 2: "

<< TestResultToString(CheckIfAborts([]() { assert(false); }))

<< std::endl;

std::cout << "Test 3: "

<< TestResultToString(CheckIfAborts([]() { sleep(100); }))

<< std::endl;

std::cout << "Test 4: " << TestResultToString(CheckIfAborts([]() {}))

<< std::endl;

and running prints:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

> build/example4

Test 1: CRASH

example4: /src/crash_tutorial/src/example4/abomination.cpp:82: main(int, char**)::<lambda()>: Assertion `false' failed.

Test 2: CRASH

Test 3: TIMED_OUT

Test 4: EXITED

> echo $?

0

This is a monstrosity that spawns threads to run a test function. If the function times out or crashes, it abandons the thread and moves on to the next test. This is a pretty silly way to do this sort of testing. There’s also a race condition that if the thread times out, but crashes later, it could effect a future test result.

I’m not sure if there’s ever a real use case to forcing a single process to continue indefinitely after a crash, but here’s a way you could achieve that.

Conclusion

While this exercise is probably only needed for fairly niche applications, I think understanding how this all works gives a clearer view of the options at your disposal for designing process termination logic.

It’s also interesting to note how this sort of error handling and diagnostics can happen in many different layers based on how you architect your system. For most cloud applications, gathering diagnostic logs and detecting crashes are handled as part of the orchestration layer that’s running on different machines in the network. You could almost build an entire “cluster” just from threads within a process with many of the same features.