Exapunks Optimization

For something a little different, I thought I’d look at the process I went through to optimize a solution in the game Exapunks.

It’s probably not a surprise that I’m a fan of Zackatronics games. Almost all of their games boil down to solving a series of puzzles in a simulated assembly like programming language with unusual constraints. I actually made a lot of typos this time around since I recently did some x86 assembly and kept typing MOV instead of COPY to move values between registers.

The gimmick for Exapunks is that your instructions are executing on tiny robots moving around inside computer networks.

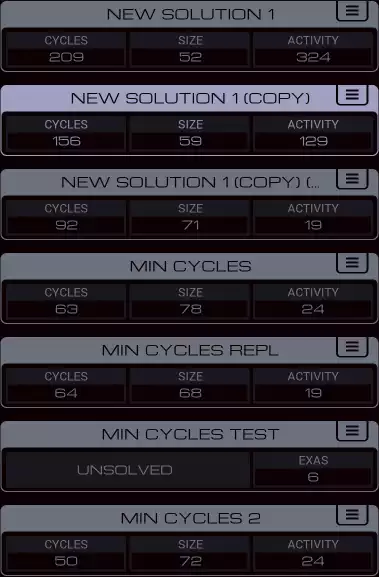

One interesting feature of these games is that they let you see how your solution stacks up against all the other players. Here’s an example:

- Cycles - The number of cycles it takes to run through the test data.

- Size - The number of instructions you wrote

- Activity - How much the bots moved between networks or attacked other bots

I usually write my solutions focusing on optimizing for cycles, as I find it most interesting. I don’t usually go back to make multiple passes at optimization unless I’m unhappy with what I implemented, or there’s an obvious major improvement. However, on the puzzle “Mitsuzen HDI-10” I decided to dig in and try to go for an optimal solution.

In the game fiction, your character is dying of a strange disease that’s turning you into a machine. You need to write a program to connect your hand to your central nervous system. There’s 3 source nerves and 3 sink nerves, and you have to move the data between them.

The most basic solution would be to have the robots move back and forth between the nerves. However, there’s also a global communication register that all the bots can read and write to for communicating at a distance. My initial solution was to have the most distant set of nerves use the global communication, and have the other two nerves handled by moving back and forth.

Looking at the data progress in the chart, you can see how far ahead the direct communicating nerve gets from the other two. The number of cycles is pretty much dominated by whichever nerve is handled slowest.

Playing through the game so far, I had never really had to master the exact way the global register was handled when multiple bots try to use it at once. The instructions for the game come in the form of a fictional zine. All it says about this behavior is:

If an EXA writes to the M register, it will pause execution until that value is read by another EXA. If an EXA reads from the M register, it will pause execution until a value is available to be read. If two or more EXAs attempt to read from another EXA at the same time (or vice versa), one will succeed but which one succeeds will be unpredictable.

I thought this would be a good chance to really understand this functionality. Here’s my codes evolution:

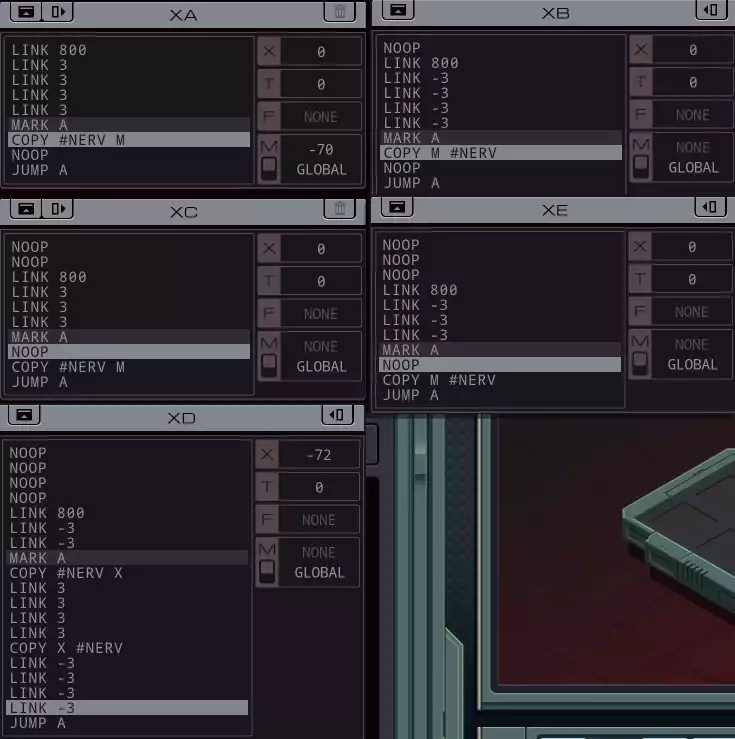

My second solution was similar to the first, but but had two nerves sharing the global register. I did this by using idle instructions (NOOP) to make sure they were out of phase:

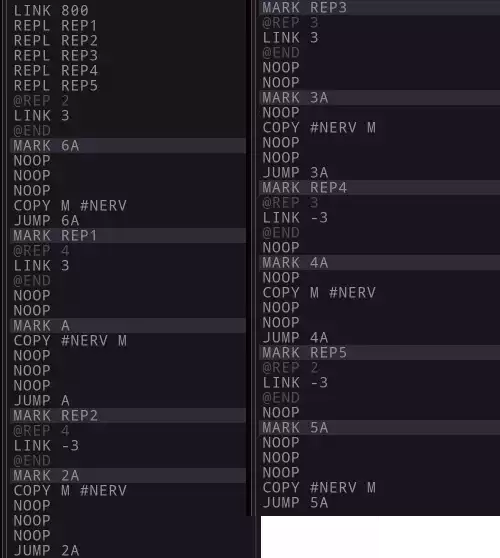

My third solution extended this so that all the bots were using the global register. However hear I hit a problem. All the NOOP I needed for padding was making the solution go over the maximum allowed size. I had to move to having all the code start in a single bot and replicate to reduce the size:

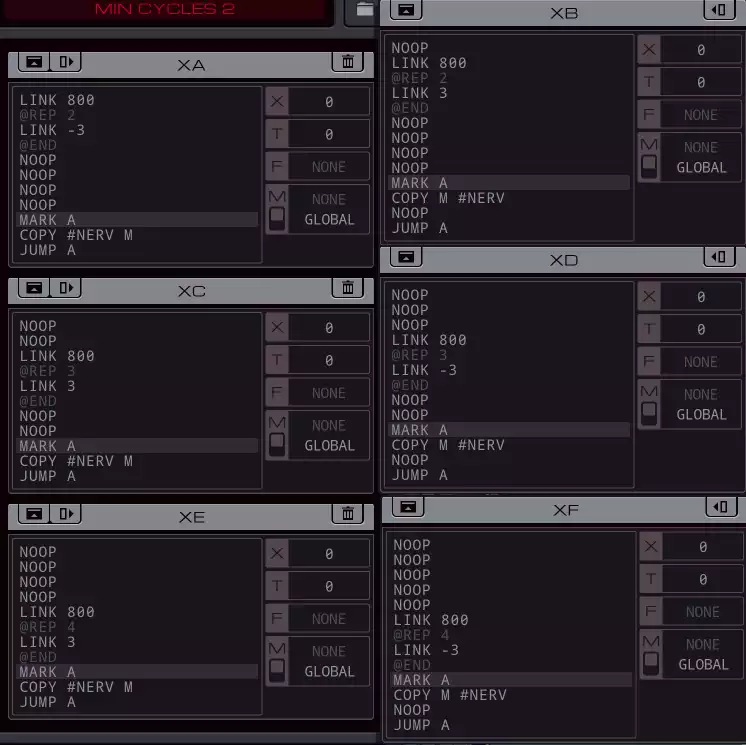

Here’s where I needed to really understand exactly how the global M register worked to get more improvements. I made a test program to just try to sync 6 bots as fast as possible as a simpler test case.

It turns out that a bot has a local M register that it can write to. Any number of bots can have values in there own M registers, and the bot will wait idle until the value is read out. When a bot reads from M, it checks if any bots have a local M value at the start of the cycle. If they do, it will use the value of one of them at random. Otherwise it idles until an M is populated at the start of the cycle.

With this knowledge I realized that it takes at least three cycles to write data from one bot to another in a loop:

| Label | Bot A Instruction | A Registers | Bot B Instruction | B Registers |

| A | COPY 1 M | M: | COPY M X | X: ? |

| (waiting for M read) | M: 1 | (COPY repeated since M wasn’t ready) | X: ? | |

| JUMP A | M: | JUMP A | X: 1 |

From there I could tighten up the loop so that each of the 3 sets of bots were out of phase with each other

Glad that after all that work I got a pretty good solution and got my red line on the score board.